A school where leadership blooms

We talked to Bianka Rodríguez, the director of COMCAVIS TRANS, an Salvadorean organization that works on improving the living standard of the LGBTIQ+ communities in El Salvador. In 2024, COMCAVIS TRANS implemented the Training School for Citizen Leadership and Participation, which services the lesbian, bisexual, trans, and queer communities of Santa Ana, Sonsonate, San Miguel, San Vicente, and San Salvador. At the school, participants learn about their rights, their advocacy power, narrative developments, social dialogue strategies, self-esteem, and ways to collective accompany each other.

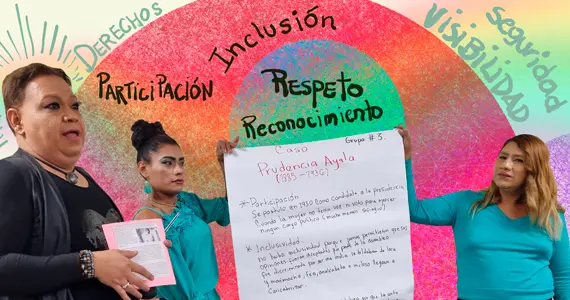

The Training School for Citizen Leadership and Participation was an in-person space for learning, empowerment, and transformation, which focused on strengthening the leadership and active participation capacities of lesbian, bisexual, trans, and queer women. In 2024, in eight sessions over four months, participants developed practical tools, critical knowledge, and support networks to confront the structural inequalities and violence they face. In addition, they worked on the creation of new narratives, collectively redefining what it means to be a woman, a feminist, and a non-normative activist.

These activities, which featured a strong analytic and reflection component, fostered an emotional rapprochement among all participants, allowing them to get to know each other, share their stories, and trace a path to overcome the challenges they face when accessing their rights.

Thirty women were selected among the nearly eighty that applied to participate in the School. All applicants and eventual participants were diverse in their gender identity, expression, and sexual orientation. Participants came from Santa Ana, Sonsonate, San Miguel, San Vicente and San Salvador, which are communities in need of empowerment and protection where COMCAVIS Trans works on issues of forced displacement.

When the school began to operate, participants shared stories that evidenced the pervasiveness of structural violence, social exclusion, and limited access to decision-making and leadership spaces.

“One of the issues we identified was the scarce or non-existent participation in processes having to do with civic, democratic, and leadership trainings. The prevalent belief is that LBTQI+ women, or the LGBTQI+ community at large, should not participate in politics at any level in the country. This is a serious issue. Despite the fact that there have been LBTQI+ candidates who have run for office, LBTQI+ folk participating in politics is generally seen as something negative. LBT folk are already isolated and cut off from support networks due to the fact that they often live in poor communities with limited resources and/or in contexts in which being openly LBTQI+ is dangerous. For example, it’s one thing to be an LGBTQI+ person in San Salvador, and a completely different thing to be an LGBTQI+ person in Santa Ana, a department that borders Guatemala. Ideed, one of the leaders [that participated in the school] shared with the group that her mother sent her to San Salvador because if she’d stayed in Santa Ana, she would have been killed for being openly trans,” recounts Bianka Rodríguez, the director of COMCAVIS TRANS.

Seeds that germinated because of the School

The School was a space of transformation for the thirty LBTQ+ women that triggered a ripple effect when, on returning to their communities, participants implemented what they called “community initiatives.”

These initiatives were self-managed and involved an investment of no more than 500 USD, but they made a significant impact due to the exchange that took place between the LBTQ+ women leaders who had participated in the school and their communities.

For example, in Santa Ana thy organized spaces to raise awareness among elderly people, who often are very prejudiced against LGBTQI+ people. The strategy was to identify the rights they had in common. Participants in San Salvador engaged companies and created a “human library,” filled with their life stories, in order to raise awareness. This expression of activism is especially relevant given that in San Salvador, discrimination against LGBTQI+ folk is pervasive in the private sector.

Estrella: A light that learned to shine brighter

Estrella was one of the participants at the Leadership School. When she arrived, she was filled with anxiety and wariness because she had been mistreated and discriminated against. Thankfully, she soon discovered that the School was different. “[Estrella] soon realized that we did things differently. She was able to communicate her identity without people referring to her with the wrong pronouns, for example. She had been in spaces before in which people called her Estrella but used the wrong pronouns. The school was an inclusive space, where we tackled these prejudices.” These healthy interactions made the school a place of solidarity for all participants.

During the self-esteem workshop, Estrella felt very apprehensive. She worried her peers would judge her and single her out because of her life story; however, as she related her experiences, she noticed her comrades were paying attention and expressing empathy toward her. She had not experienced that in the past. She later said that having other women listen to and understanding her made her feel fulfilled in a way she had not felt before.

In one of the practical workshops at the School, Estrella took on the role of community promoter and although she had no experience in planning initiatives (nor did the rest of the participants), they put together the proposal. They decided to tackle different the kinds of violence faced by LBTQ women and put together an awareness-raising campaign.

What was deeply transformative for Estrella and her colleagues was that in the process of co-creating the campaign, they listened to their experiences and discovered that violence does not affect them all equally and that each of the identities and orientations suffers different forms of violence in specific ways. This helped them communicate more effectively as they worked on the campaign. Estrella later commented on the effectiveness of succinct messaging whereby they could convey complex experiences; for example, a photograph could communicate much more than a long text.

The campaign was Estrella’s final project and marked the completion of the leadership school. She departed filled with inspiration, a broader perspective, and satisfaction at having learned to develop and use practical and concrete tools to address the issues that affect them in their communities. Estrella and her comrades witnessed their leadership bloom, and this motivated them to apply what they had learned in their communities. “That was the moment when they all assumed their role, and they started coming up with initiatives, ‘let’s do one in Santa Ana!,’ ‘How about one in Sonsonate?,’ ‘Let’s start something in San Miguel!’ That’s how they began organizing collectively.” (Bianka).